Find in store:

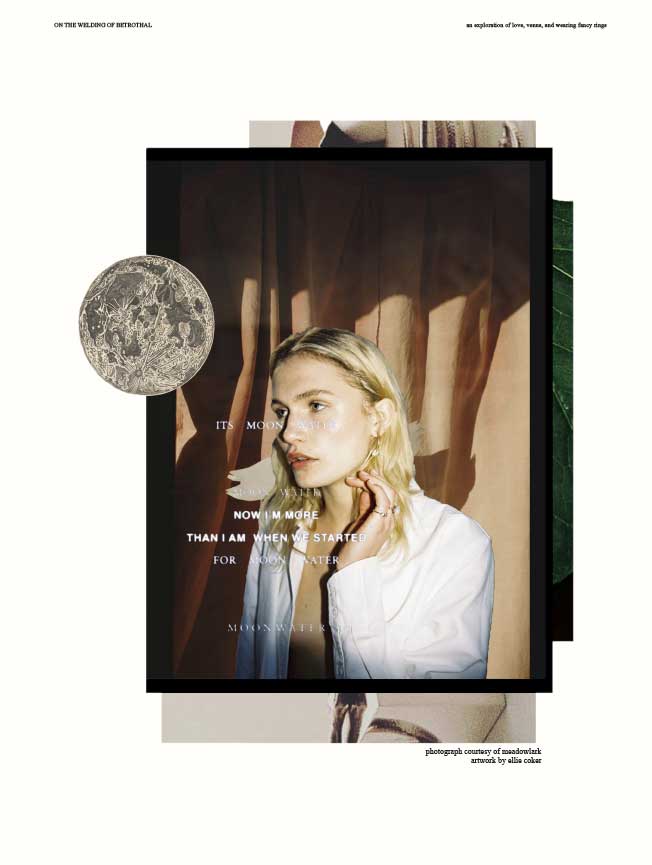

This interview is one of the best we have had the pleasure of doing.

We think it tells you a lot about us and what informs Meadowlark.

First published in Jane by the Grey Attic in December 2017

Truman Capote taught me a lot about diamonds. He taught me that it’s tacky to wear them before you’re forty, and that even then it’s risky. They only look right on really old girls, women like the late Russian actress Maria Ouspenskaya. Wrinkles and bones, white hair and diamonds; the finer things we can all look forward to in life. But of course, that’s just one opinion. And there’s a lot more to be said about diamonds than what is found within the pages of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Most of us have our own reasons for wearing the jewellery that we do, and often times, that reason has something to do with love.

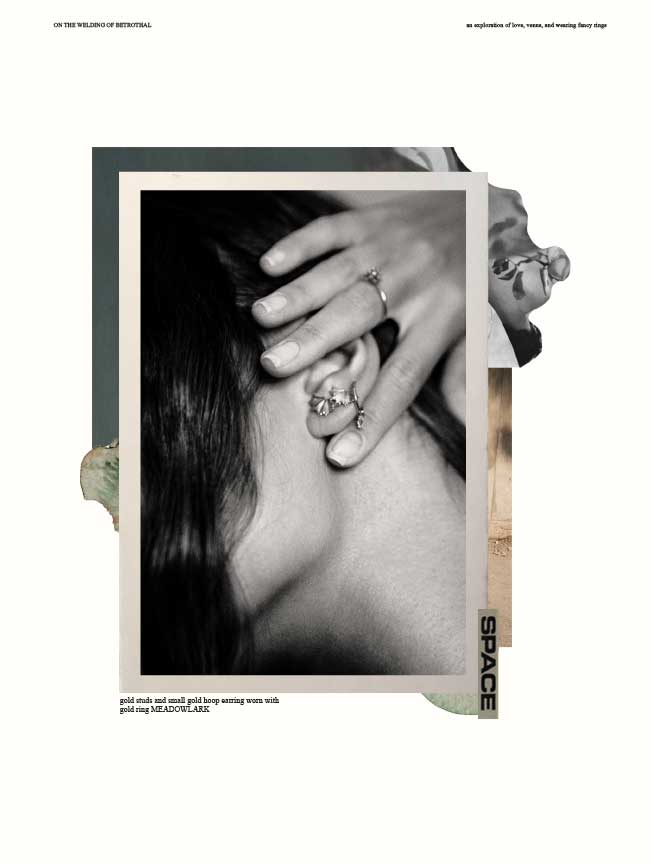

Two people who know this all too well are Claire Hammon and Greg Fromont, the founders of cult jewellery brand Meadowlark. Working from their New Zealand-based atelier, the couple are in the business of making meaningful jewellery for self-possessed men and women; tiny artworks designed to be cherished forever. But their work isn’t about excessively bejewelled rings or offensively large gemstones. Nor does it honour tradition, straight-up prettiness, or the pursuit of aesthetic perfection. Guided by their intuition and inspired by the obscurity of objects such as vintage lamps, Hammon and Fromont challenge conventional notions of romantic jewels, inviting us to experiment with the tangible tokens of love and romance.

Kathryn Carter: What is your earliest memory of noticing somebody’s jewellery?

Claire Hammon: Playing with my mother’s beautiful diamond rings is a strong memory for me, she had a lot of vintage pieces handed down to her—lots of diamonds and rubies and emeralds.

Greg Fromont: My mother had various pieces of jewellery too. She had a particular anchor brooch, made of jade I think, but with a gold top and bottom piece.

Why do you think we give the gift of jewellery to symbolise our love?

There really is no other gift that lasts for generations. I [also] think, because we often wear a piece every day for many years, it feels like the jewellery is on a journey, and maybe we want to be on that journey with our loved ones in our own little way. There is some sort of personal transference; it’s like the person is with you. I think it used to be far more prevalent as a symbol of love in the more distant past, but [used] in the form of mourning, as the mortality of humans was so [much] worse than it is today.

How does a piece of jewellery qualify as being romantic? Is there a criterion? A formula you use?

I think when your partner gives you a piece of jewellery it’s always romantic, no matter what the piece is. Just the thought that they want to give you something that marks a time is romantic… I don’t think the style of the piece has to be anything in particular—it just needs to suit the wearer.

One of the first uses of a diamond ring to signify engagement was by the Archduke Maximilian of Austria during the Renaissance in 1477, upon his betrothal to Mary of Burgundy. People have been giving diamond rings to their loved ones ever since. How do you think our ideas of wedding and engagement rings have changed over time? What do you think this reflects within our culture?

I really don’t think our idea of wedding and engagement rings has changed that much to be honest. There are definitely still people who care about the status of a big diamond, but we are seeing more and more coloured stones and different designs because people want to be authentic and unique, [in keeping with] what they really like. I totally agree with Claire. The idea of weddings and engagement isn’t changing terribly, but the tradition and culture that was previously surrounding it is.

Your current engagement ring collection features thunderbolts, skulls, and snakes. These motifs aren’t at all typical for this type of jewellery in particular, yet the inclusion of gemstones in each design still makes them feel suitably bridal. What do these motifs—thunderbolts, skulls, snakes—mean to the two of you? Why was it important to you to include these design tropes in (what could be considered) your most “traditional” pieces?

Our reasoning behind these motifs was really to offer an alternative to traditional engagement rings… for people who value individuality over tradition. Snakes have so much history in jewellery, from Cleopatra to the engagement ring worn by Queen Victoria. For us they symbolise eternal love. I would love to make so many more serpent styles. They’re an alternative to a tradition; that’s what makes them more interesting. They’re a crossover and a mixture, an inclusion of popular culture and historical references. They add comment and flavour to an age-old idea of monogamy.

Do you feel like the permanence of jewellery—as compared to the perishable nature of flowers and chocolates—is part of the reason why we often gift rings, necklaces, etc. as a token of our love?

Yes, but I feel like there is also a level of detail in a piece of jewellery that can express an earnestness of love.

Do you feel like wedding, engagement, and promise rings could be described almost as a collaborative embodiment of the love two people have for one another? Like a tiny artwork that only two souls will ever truly understand?

Yes definitely, and especially when a couple chooses or customises a piece just for them, so that no one else has the same thing. We love to add tiny elements to custom rings that only the couple know about.

Tell us about one of your favourite romantic gestures from history— from reality, a film, perhaps a novel?

The song “Exit Music (For a Film)” [by Radiohead] has always really affected me in this sense. For me it [always] represented a couple joining together and escaping some repressive hierarchy. It evokes [the idea of] personal struggle and sacrifice in order to pursue a relationship. I’ve been listening to that song since 1997 on and off, and only recently found out it was written for Baz Luhrmann to accompany his film Romeo + Juliet. Before finding this out I always ascribed an Eastern European flavour to the imagined story in my head, and assumed the protagonists lived [in the end]… which I feel is more romantic than the outcome of Romeo + Juliet.

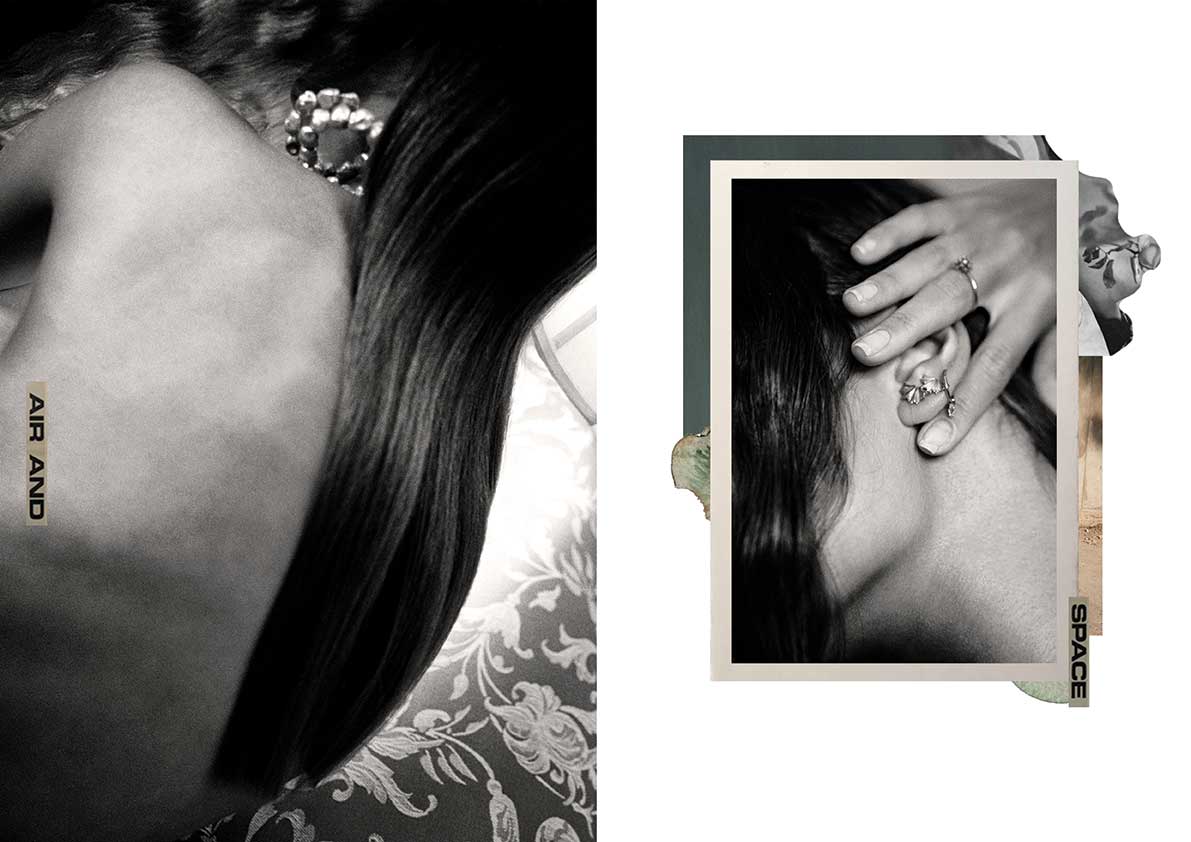

The act of putting a piece of jewellery on someone else is quite sensual. Why do you think this is?

Well, that depends on what it is. [Putting] a necklace [on someone] is similar to zipping up a woman’s dress, I think. There is an aspect of vulnerability there, of exposing a sensual part of the body. Jewellery serves as a connection point too, a reminder of love, which is strengthened if the giver is also the one putting [the piece of jewellery] on.

Art, fashion, and your background in streetwear design and skate culture influence your designs. How would you describe the Meadowlark aesthetic?

It’s hard to describe our aesthetic, even though I am the gatekeeper of it. I think it is feminine but with a toughness; it’s quiet but confident. I seem to always describe it as a push and pull between dark and light. It is overall pretty but retains a certain edge.

What really inspires you?

I think I’m mostly inspired by trying to be better. A better, kinder, thoughtful person and the best designer I can be.

I’m still trying to figure that out. It’s like I’m trying to distil a nuance in things that ticks all the right boxes. There is an aesthetic, and I don’t know what its called, but it exists in very specific clouds in a type of light, or in very specific songs, or in particular drawings or design.

Many contrasting motifs appear in your collections, from flora and stars to daggers and thunderbolts. Is this juxtaposition between elegance and edginess something that you consciously think about in your designs?

I think it’s just what comes out of us. We aren’t really conscious when we design; it really does come from our souls, and often I have an epiphany that will become a collection or a design. Meadowlark is an unconscious extension of our own personalities, and I think we both tend to create powerful symbols [for that reason].

You describe your jewellery as tiny artworks. Does this reflect how you create each piece? Do you think about each ring, neckalace, and earring as an artwork first and a wearable item second?

Yes, often that first bold piece is the artwork, and then we pull that down into a more wearable offering. To us they are tiny artworks because it’s a deeply personal process we go through to birth a collection from ourselves. I’m also very intense about every angle being perfect.

Do you ever go out wearing no jewellery at all? If so, do you feel like something is missing?

I am always wearing jewellery; I sleep with all my earrings in. I definitely feel like something is missing if I don’t have a ring on my finger. I currently have three rings [I wear], one of which is my wedding ring. The other two I swap, depending [on how I feel]. I definitely feel their absence if I forget to put them on. They are an expression of important aspects of my life, and of who I am.

Those who lose a piece of jewellery they’ve been wearing for years often say that they feel “naked” without that particular piece. This says a lot about the kinds of relationships we form with jewellery. What do you think it is about jewellery that causes us to bond so closely with it? Is it merely the tactile nature of metal to skin, or do you think there’s more to it than that?

The human relationship with jewellery is beautiful, and I feel very lucky to be a part of it. Buying a piece of jewellery for yourself is the best gift, and receiving it from someone you love imbues meaning into it more than any other gift I can think of. I think wearing it on our skin is part of the bond, but I believe there is more to it—I think metal, being from the earth, and metals being within us is a part of the reason it feels like more of a connection. Often jewellery marks important stages in our life too. I still have a collection of jewellery from throughout my life, and each piece has a story, a place I purchased it, a person who gave it to me, a particular birthday, just so many memories.

It has a lot to do with the circumstances of receiving a piece of jewellery, but I think it also says a lot about how our minds work. I think wearing something every day makes it a part of your psyche fairly quickly. The idea it represents becomes repeated in your own consciousness over and over and imprints itself onto you. It works in reverse too; events and ideas rub off on or become imbued into pieces of jewellery. That’s what makes heirloom pieces so special, and other people’s discarded engagement rings after a divorce so repulsive.

Your latest collection, VENUS, is inspired by love, as well as by Botticelli’s Renaissance masterwork The Birth of Venus. Can you remember the first time you saw this painting? How did it make you feel?

I can’t remember the first time I saw it—it feels like an image that I’ve seen so many times throughout my life—but for a long time I didn’t know what it was. I seem to remember doing a little bit of study on it when I did art history at school. In some ways, it is a piece that is rebellious in that it was bucking the trend of the Renaissance paintings to only be of a Christian nature. Botticelli was a rebel.

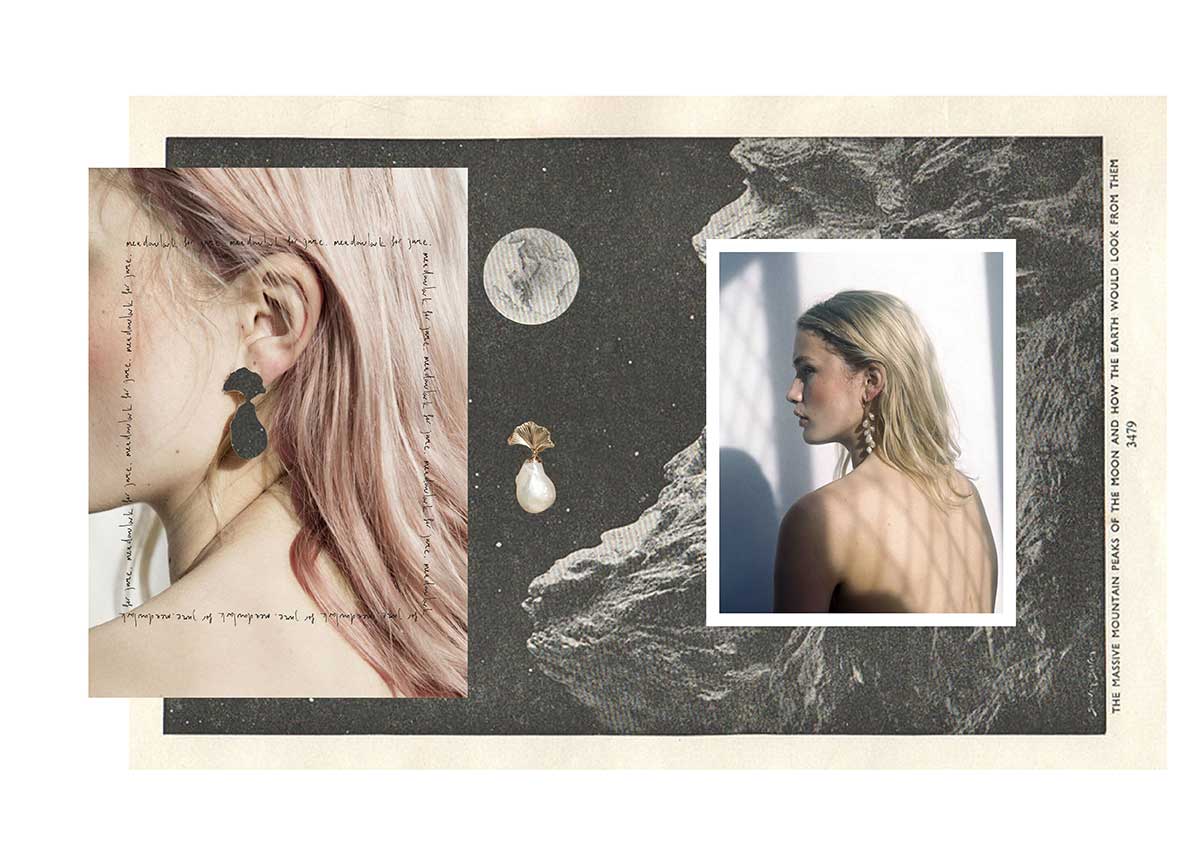

VENUS combines unusual materials like baroque pearls, grey diamonds, and pink and green sapphires with shapes that relate to the opulence and grandeur of Renaissance and Baroque art, Gothic iconography, and ’80s high glamour. Tell us about the kinds of jewellery men and women wore in these times.

Certainly the jewellery of those times was different to what we’ve created in this range. The references cross over from various art forms to come together as a whole. There are Gothic halos and ’70s lamps and gifts from the sea. There is glitter and glamour, and glossy, sugary love symbols. The range is a clipping from different but related vogues throughout history, but we are all going round and round in circles. Ideas of glamour and romance and love, and how those things are perhaps divine, were not so very different during the Renaissance and the ’70s and ’80s, or even the Classical period. The iconography crosses over, because the human mind is repeating the same thoughts throughout history, although the culture surrounding it is very different.

A fan-shaped 1970s vintage lamp by Carlo Giorgi also partly inspired the collection. Do abstract objects often spark ideas for you?

I am obsessed with art and sculpture and mid-century design, so I’m certain that influences me, but I think this is the first time we have been so strongly and directly inspired by a single design. [The lamp] is a gingko leaf … Nature always appeals to our design senses. Our ideas come from a mishmash of visuals. Often the ideas that lie around the object are important—in this case, what they resemble and look like. It’s not very conscious though; it’s a thing that happens as part of the process sometimes.

The range also includes a classic line of heart-shaped and diamond-set pieces, with some plain bands inscribed with bold, heartfelt declarations of love in English and French. Is this the first time you’ve incorporated text into your pieces? What inspired you to do so?

Yes, this is the first time we’ve used words. I love words and it felt like the right time. These rings in particular were inspired by my obsession with the French language. I’ve been learning French for a while, and it just felt right to incorporate it.

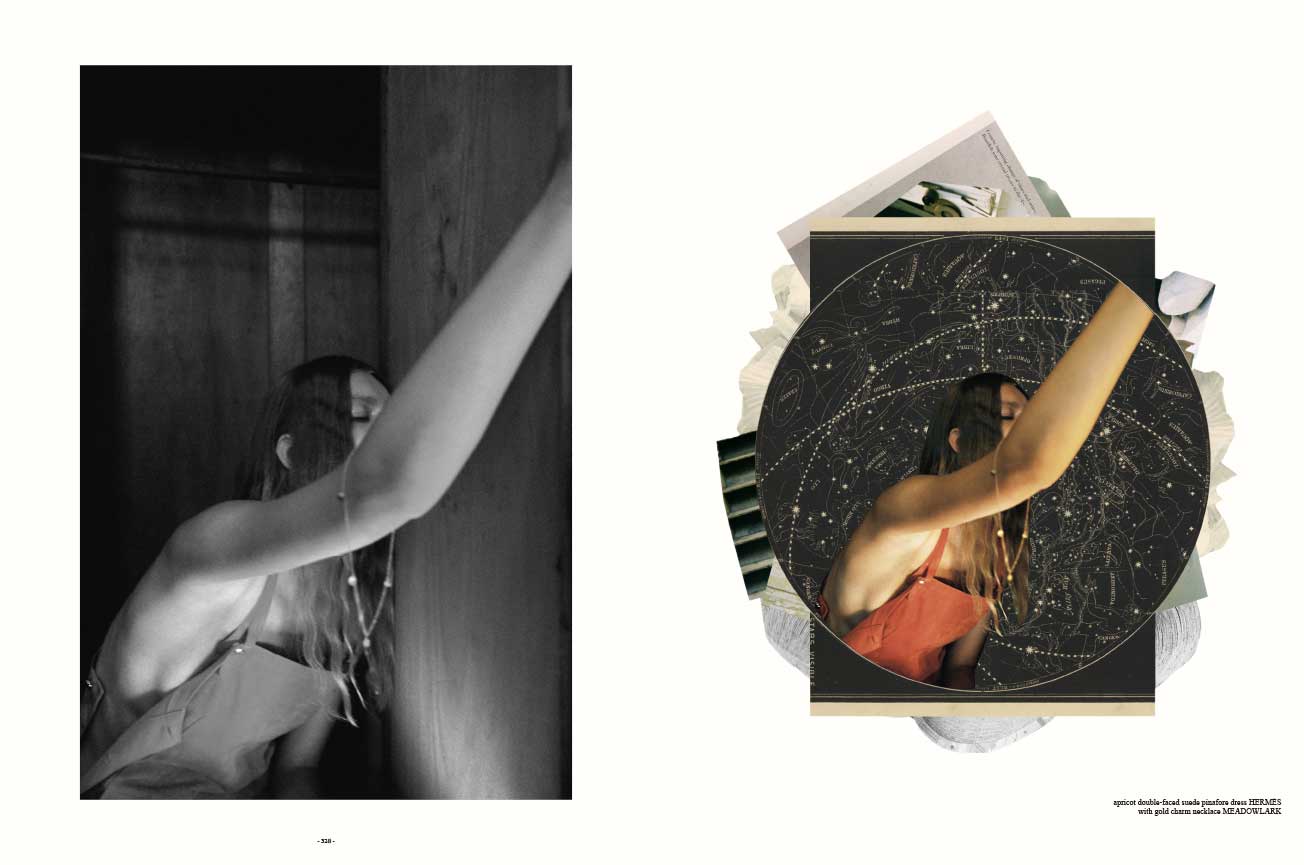

How do you start a piece of jewellery? Do you start with a theme, a daydream, maybe a material or a gem you’ve come across?

It really is different every time. We don’t usually start with a theme, as it feels too constricting for us. [For VENUS] the pearls were definitely inspired by the material itself—they are wonderful to work with. Often I just sketch and see where it takes me. Sometimes I start with a silhouette, [or] sometimes I see things in a really strange way, like I will see something on the street and as I get closer it [looks] completely different, and that misinterpretation will become an inspiration. And sometimes I see only the negative space in things, which can be a strange feeling but the beginning of an idea.

The jewellery we wear has changed dramatically over time. Do you ever look to the past when researching your collections? Is there a particular period you return to for inspiration?

I really don’t like the past; I try to never look back. I strive to always go forward to design better pieces than the last time. In some ways we find it restrictive. I think the past is important because it is littered with important ideas, but they range across many art forms. I was always enamoured with Art Deco, and very specific parts of Art Nouveau, but I think it was more about a certain composition of parts. Also, these periods represented a new age of modernity and moving away from tradition and into a more liberal—and commercial—mindset. But this [interest] has less and less to do with how we actually design. It’s there, but the designing we do has to be our own journey.

What do you love most about jewellery as a form of self-expression or adornment?

I love that it’s a very quiet form of self-expression; it’s not about looking a certain way or fitting into a certain style. You can dress any way you like and jewellery is a little cherry on top that others may not notice but you know you have—this special totem close to you.

Yes, I agree. It’s [really] a tiny keepsake designed for a very small audience. It is a concentration of a lot of thought and creativity in a tiny space.

I have to ask: what is the meaning behind the name Meadowlark?

It comes from a quote by Ambrose Bierce [that] ‘the metallic note of the meadowlark suggests the clashing of vibrant blades’.

Would you like to be buried in your jewellery? If so, what pieces would you like to wear?

I don’t want to be buried in my jewellery. I would like to see my pieces handed down to my daughter and further generations.

I think I would like to be buried with my wedding ring on. It’s not something I’ve ever considered before, but I take comfort and security in my wedding band, so I can’t imagine I’d want to face eternity without it. The ring on my other hand is about facing today’s life challenges, so I don’t feel it [would be] appropriate in death… Weird.

I would like to be able to keep a part of Greg if he passes before me, so we might have to discuss this further (laughs).

Stylist: Annika Hein Model: Anya Make-up: Teneille Sorgiovanni Hair: vic Anderson